Sand Dwellers – My Least Favorite Monster

Sand Dwellers – My Least Favorite Monster

Designer Diary by Sandy Petersen: Skin Deep

By Sandy Petersen

A question I get a lot in interviews is “Which Lovecraft monster is your favorite?” but something I am never asked is “Which monster is your least favorite?” If I was asked this, I would unhesitating have answered “Sand Dwellers” at least, until last year, when I designed the new Cthulhu Mythos Saga Skin Deep which features them. But why do this? Let’s examine.

Now very little is known about these obscure creatures. They first showed up in “The Gable Window” by August Derleth. So Derleth gets 100% of the credit … and the blame … for the Sand Dwellers. They’re not even the story’s main threat. Instead, the hero has a magic window. In one scene, he sees the American Southwest. Some creatures, identified as Sand Dwellers, emerge from a cave. These are emaciated humanoids, with gritty, sand-like skin, huge claws, and koala-like heads. I have to say that the koala bear head was a sticking point for me. While I don’t think koalas are super cutesie they are certainly not frightening. This is a good example of why August Derleth is weaker in horror than Lovecraft. When Lovecraft invents something, it’s terrifying in concept. When Derleth invents something, it is lacking. Anyway, as the Sand Dwellers scuttle forward, tentacles start to emerge from the cave, and then the hero gets scared and shuts off the gable window, which works like a TV set.

What do we get from this?

The Sand Dwellers live in the American Southwest.

The Sand Dwellers seem to be nocturnal and subterranean — they are seen exiting a cave at dusk.

The Sand Dwellers seem willing to work with other beings as witness the unseen tentacled critter.

Really my problem with Sand Dwellers is that they seemed really boring — just skinny little servant critters from the desert. Maybe Derleth thought that the ocean had Deep Ones, the arctic had Wendigoes, and outer space had Byakhees, so he needed a desert monster for completeness. But he didn’t add anything interesting about them.

In 1998, Adam Niswander wrote a horror novel titled “The Sand Dwellers”. It is mostly psychological horror, and the actual Sand Dwellers don’t make much of an appearance, though perhaps their psychic energy is being applied. Mr. Niswander doesn’t use much of Derleth’s version — probably because Derleth didn’t give him much.

My opinion of Sand Dwellers was so low that one year, when we ran out of candy o Halloween, I gave trick-or-treaters vintage Grenadier models of Sand Dwellers. So there you are. I had such little regard for these creatures that I gave them away to children I didn’t even know.

Move ahead to current times. I am proud of the fact that I have now produced miniatures of practically every Lovecraft monster. I have minis for the King in Yellow, Gnoph-Kehs, Serpent-Men, Azathoth, Dholes, Bholes, and Rhan-Tegoth. I have some really obscure ones such as the sorcerers of Yaddith and Robert Bloch’s Dark Demon form of Nyarlathotep. I also have many of Ramsey Campbell’s inventions such as Daoloth, Eihort, and the insects from Shaggai. The most important missing creatures are Brian Lumley’s creations. Mr. Lumley declined to sell us the rights, and I respect his decision. I suspect he bears some ill-will from the 1980s when Chaosium ignorantly published his creatures without permission, and who can blame him?

But one figure I have not produced are the Sand Dwellers. They’re not in my Petersen’s Field Guide (1987). They’re not in the huge panoply of Cthulhu Wars. And they’re not in Sandy Petersen’s Cthulhu Mythos for 5e Fantasy.

Last year I started brooding on this. Not because I felt I owed anything to the Sand Dwellers, but it seemed an interesting intellectual exercise to make Sand Dwellers scary. I dedicated myself for a few weeks to concentrate on Sand Dwellers, and the purpose of this Designer Diary is to discuss the choices I made to accomplish this task. Basically I had to create a biology and culture for these beings, plus fit the limited background we do have. I feel I succeeded. They match everything already known about them, but are now far more interesting as a monster.

Sandy Tries to Make Sand Dwellers Scary

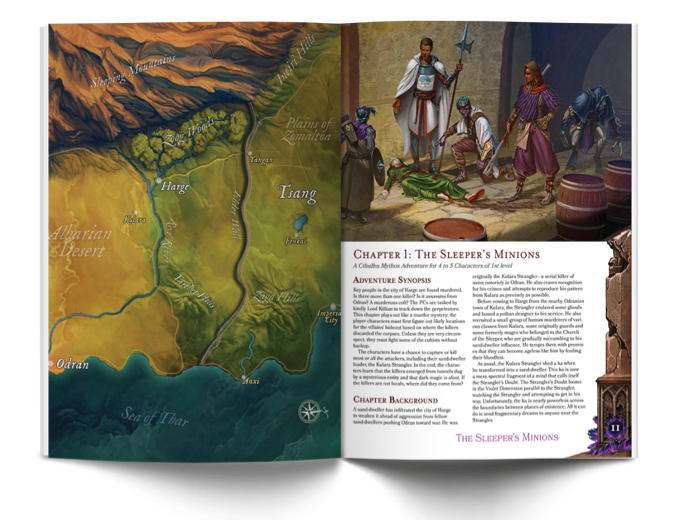

My ultimate goal was to incorporate Sand Dwellers into one of my Cthulhu Mythos Sagas for 5e. So I considered first, the fact that they appear in the American Southwest, which is an extremely well-traversed area. You’d think someone would have encountered them. Deep Ones live under the sea. Gnoph-kehs on the Greenland ice. But I’ve driven through the Sonoran desert scores of times. Why don’t I see Sand Dwellers? (Besides the fact they don’t exist.)

My first decision was “What if Sand Dwellers don’t live in the Southwest?” What if instead, they live on another plane of existence, but can sometimes travel to ours. I don’t want to make them just another dimensional wanderer so I posit that this is done with difficulty. In this interpretation the “Gable Window” hero sees them coming out of a cave because that’s where there was a portal. Perhaps the tentacle monster following them helped create the portal. I gave their plane of origin a name — the Violet Dimension.

To give them goals and challenges, I decreed that Sand Dwellers can return to the Violet Dimension at any time, perhaps automatically when they die, thus leaving no trace behind. But they can’t leave the Violet Dimension except via a magic means. This explains why the creatures are rarely seen. And why when they commit an outrage, they can escape, leaving no trace.

Now Niswander’s novel indicates that the Sand Dwellers can affect human minds. I like this because of course it is scary. But I want them to do it with a purpose. As I pondered this I also thought about their described body-form — extremely thin, weird crusty skin, and odd heads. They are surprisingly humanoid for a Lovecraftian monster, most of which are based on invertebrates or even plants. When a monster resembles people in Lovecraft, it’s for a reason. Deep Ones resemble humans so they can mate with us. Ghouls resemble us because they are derived from us. So the Sand Dwellers must also have a connection. Then it came to me.

What if the sand dwellers literally emerge from us? In other words, the Sand Dweller gestate inside a human host, using the host’s body as a sort of cocoon. The Sand Dweller flesh grows around our bones. When they are “ripe”, they emerge. Thus, they are emaciated-looking — they must be narrower than a human to use us to pupate.

How does a Sand Dweller get into a human? It’s simple — psychic invasion, The Sand Dweller send its mind from the Violet Dimension to begin a takeover. The mixture of Sand Dweller and human mind makes the human seemingly insane. My theory is that the human seems normal externally, but inside, the monster’s blood lust basically turns the human into a serial killer. Or perhaps Sand Dwellers target serial killers. Anyway, my Cthulhu Mythos Saga, named Skin Deep, starts out about a serial killer.

As the human host commits more murders, the Sand Dweller grows stronger. Eventually it seizes full control, and only uses the human as a shell. But that human flesh must soon die and begin to rot; when the Sand Dweller has to cut its way out.

So now we have creatures that slowly turn humans into maniacs, but eventually emerge into our world. What else? Remember the big tentacle monster from “The Gable Window”? This creature didn’t necessarily seem like a Great Old One, but it was certainly a formidable entity. I think the logical answer is that the Sand Dwellers adopt powerful creatures as protectors. I’d guess dangerous, but second-tier beings such as Bokrug, Byatis, a Ratbatspider, or a really big Shoggoth. A being weak enough to appreciate the patronage, yet an effective defender.

So there we have the Sand Dwellers as I see them. They seep into you from Outside and replace you with horror beyond imagination. Once enough have arrived, they bring in even more fearsome beings to accompany them. Our only hope is that, eventually, they will leave without a trace.