Why doesn’t Sandy play Call of Cthulhu in the 1920s setting

Call of Cthulhu (the RPG) was the first ever game based on H.P. Lovecraft’s works, and it’s considered the most successful horror game of all time. Since its release in 1981, a popular way to enhance the role playing experience has been the introduction of miniatures, used to represent the characters in the game.

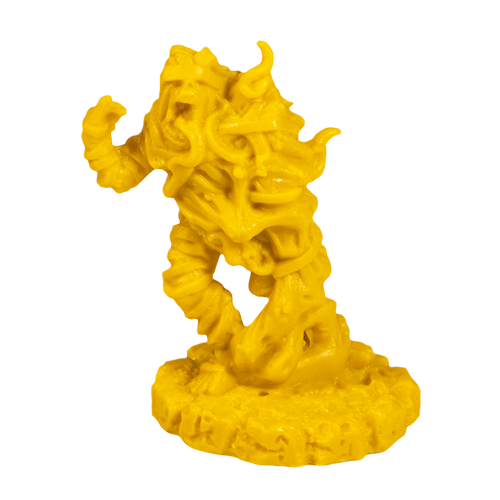

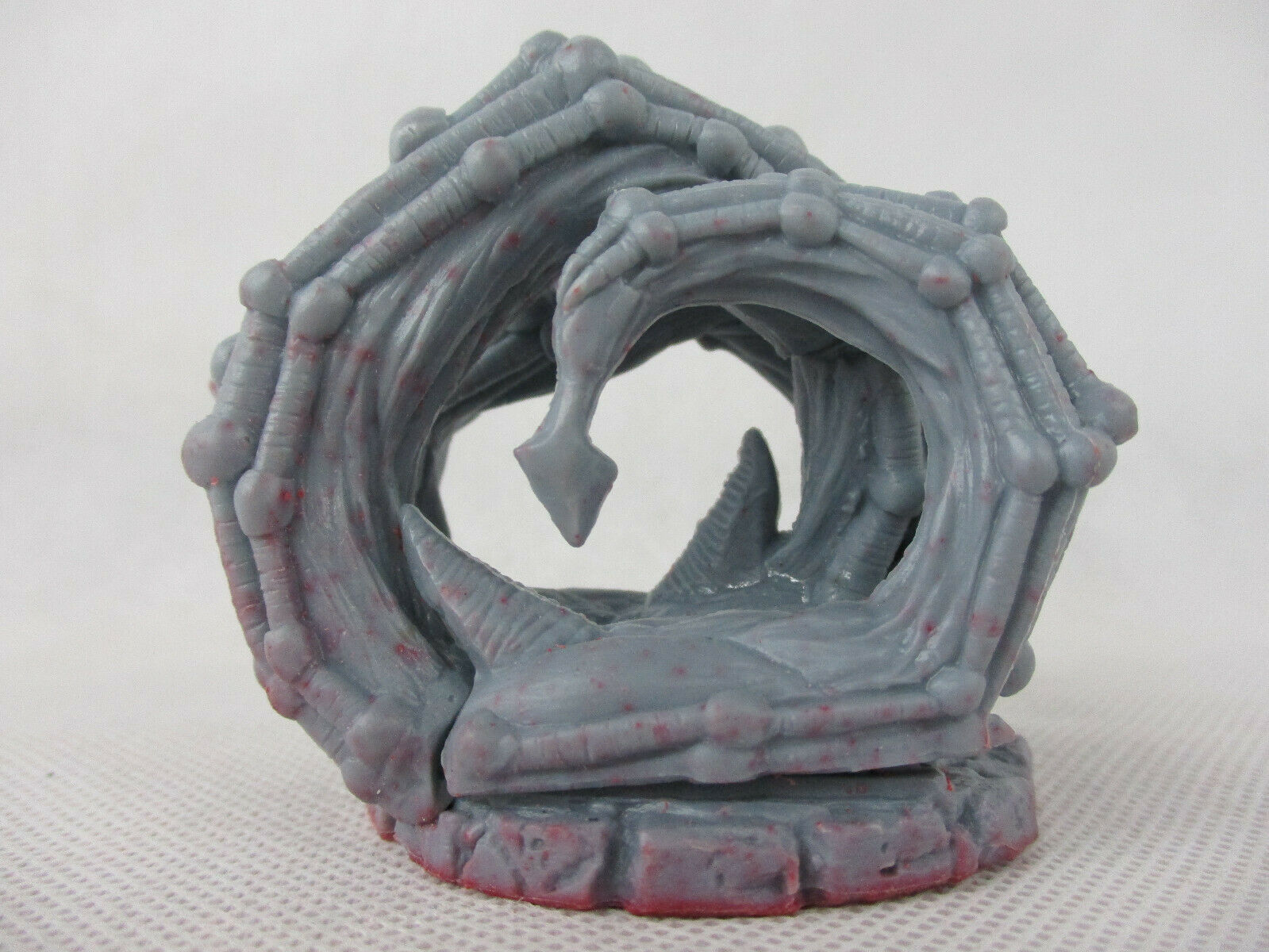

Petersen Games has now released our own line of Cthulhu mythos miniatures, previously only available by ordering our board games. While you are considering adding them to your role-playing activities, here is some background behind Lovecraft’s popularity, how I came to design CoC, and why I don’t play it using a 1920s setting.

How did Lovecraft become so Popular?

Lovecraft was a forgotten author – except among authors and a tiny loyal group of fans. He was reviled by critics, those few who read him, and the assumption was that his stories were terrible. His popularity started in 1981, when Call of Cthulhu the RPG came out. Then, starting in 1985, some good films also started coming out, based on Lovecraft’s works.

Also, in the 1980s S. T. Joshi, a literary critic, started the re-evaluation of Lovecraft as an author. He more-or-less singlehandedly redeemed Lovecraft in the eyes of arrogant academics.

These three factors combined. My game moved through the roleplaying audience – even people who hadn’t played it had heard of it. Stuart Gordon’s movies moved through the horror geek audience. And S.T. Joshi influenced the intellectuals– he also successfully edited new editions of Lovecraft’s books, with HPL’s original language.

All these things happening simultaneously popularized Lovecraft in a way that had never happened before. I’m not sure which was the most important – probably Joshi had less effect than either me or Stuart Gordon, but all of us spread the news. Today, Lovecraft is well known. Games, books, films, toys, all thrive thanks to this.

I am proud to be the person who started this renaissance, so let’s discuss how my games did this, and why I don’t play in the 1920s, as the game seems to prefer.

How I Came to Write Call of Cthulhu

In 1980, I had started writing a few supplements for Chaosium. The biggest one was Gateway Bestiary, which actually misspelled the name Runequest on the cover. In this product, I introduced some Lovecraft monsters – shoggoths, deep ones, and so forth. I loved Runequest and played it plenty.

The difficulty was that Chaosium had the rights to publish a Lovecraft game, but they had no respect for Lovecraft’s writing. They realized if they wrote it, they would not do the game justice. Simply because they had contempt for Lovecraft, they realized this contempt would seep through the game, and taint it. You’ve seen this happen in other genres, such as movies, when a director doesn’t respect what he’s doing.

That’s why they hired me to write the Call of Cthulhu. They didn’t tell me of their lack of respect for Lovecraft. But they knew I loved it and would do the best job I could. That’s what they wanted. The best job.

But … Chaosium also knew that to do a full roleplaying game would require them to put in lots of work into it anyway. How could they somehow get a love for the topic? How could they find interest in the work of this so-called hack?

Why I don’t Play Call of Cthulhu in the 1920s

Chaosium’s genius was that they said, “The stories mostly take place in the 1920s. The 1920s are cool. Let’s set the game then!” and thus the 1920s era for Call of Cthulhu was born. They did a whole great big sourcebook for the 1920s and put it in the box. Folks loved it. Not just horror, but the 1920s.

Because they’d hung their hat on the 1920s, they were able to love the topic and get into it. Because they had a Lovecraft fan write the rules, I was unfettered and able to make it as creepy and horrifying as I liked.

Now, you must understand that Lovecraft wasn’t writing in the 1920s. He was not creating nostalgia – he was creating horror and science fiction and incorporating the latest discoveries. His tales feature airplane exploration of Antarctica, submarines, ultraviolet light, the discovery of Pluto, and so forth. He was cutting-edge. So, to me it was natural to set Lovecraft’s stories in the modern world. And I’ve usually played with that assumption.

So, when I played a game of Call of Cthulhu, mostly I ignored the 1920s setting. Sure, it was ostensibly 1920s, but the players drove cars, and carried guns, and there were police. It was close enough to the modern time that usually it made no difference. It gave me an excuse to force the players to travel overseas by boat, which was cool, and occasionally in dark corners of the earth there were groups or tribes no longer in existence.

But generally, I played it without reference to the time period. Not so the rest of the Chaosium team. They exulted in talking about the quaint old cars, flapper costumes, zeppelins and so forth. But the important thing is we all had fun, and so did the gamers.

Making Horror Horrific

In short – horror to be most effective has to be brought home to the players. In general, it’s harder to imagine yourself in the 1920s, because we never lived then. That becomes an additional obstacle to feeling terrified.

If you can set the horror in the same time as the players themselves live, it’s that little bit easier to scare them. It just gives you an edge, and I want all the advantages I can use.

But in reality, you can set horror in any era you choose. Just remember that if it is not set in the here-and-now, you may have to do a little extra work.

But that little extra work may be worth it!

About Sandy Petersen

Sandy got his start in the game industry at Chaosium in 1980, working on tabletop roleplaying games. His best-known work from that time is the cult game Call of Cthulhu, which has been translated into many languages and is still played worldwide.

He also worked on many other published projects, such as Runequest, Stormbringer, Elfquest and even the Ghostbusters RPG, and was instrumental in the creation of dozens of scenario packs and expansions. He also acted as developer on the original Arkham Horror board game.

In 2013 he founded Petersen Games which has released a series of highly successful boardgame projects, including The Gods War, Evil High Priest, and the much-admired Cthulhu Wars. His games have sold tens of millions of copies worldwide, and he has received dozens of awards from the game industry.